There’s something special about Japanese pottery that distinguishes it from its western counterpart. That something is not only its looks, but its design philosophy, East Asian tradition and the variety behind it. Japanese and European influences are merged to form tableware that can be not only beautiful and intricate, but also utilitarian and minimalistic. Between these two poles (intricate vs. minimalistic) all sorts of variations exist, depending on the style of a particular region and the individual craftsman.

Yakimono journey in Japan

Today we’re going to take a look at the different styles and types of pottery in western Japan, meaning everything in between Nagoya and Okinawa. Depending on the region there exist different traditional patterns, colors and glazes. We are going on a journey through Japan with stops at the most famous hot spots for pottery. On the way there we’ll supply you with plenty of information concerning what makes a particular type of pottery special and a regional overview (of famous foods and places along the way). If you’re already interested in Japanese ceramics and porcelain, maybe you’ve already heard names like arita-yaki, seto-yaki or mino-yaki, which are some of the most famous styles. In any case, get ready, because we’re about to dive in deep into the world of beautifully burned clay!

- Yachimun from Okinawa

- Satsuma Yaki from Kagoshima

- Ryumonji Yaki from Kagoshima

- Hasami Yaki from Nagasaki

- Arita Yaki from Saga

- Koishiwara Yaki from Fukuoka

- Onta Yaki from Kumamoto

- Tobe Yaki from Ehime

- Bizen Yaki from Okayama

- Tanba Yaki from Hyogo

- Shigaraki Yaki from Shiga

- Tokoname Yaki from Aichi

- Seto Yaki from Aichi

- Mino Yaki from Gifu

- Kutani Yaki from Ishikawa

If you are coincidentally looking for some new, handmade ceramics or porcelain, why don’t you stop by at our shop? You can find truly unique tea-cups, plates and vessels for your next sake tasting there. But now on to the different ceramics of western Japan!

Traditional porcelain and ceramic from Japan

Of the list above, six manufacturing traditions reach back around 900 years and are therefore called the “traditional Japanese methods”. Those are Seto-yaki, Shigaraki-yaki, Bizen-yaki, Tanba-yaki, Echizen-yaki and Tokoname-yaki. Other methods originate from the Sengoku-period, when Toyotomi Hideyoshi (Shogun in the late 16th century CE) launched two invasions of the Korean peninsula. The military campaigns failed, but not without Korean master craftsmen being “invited” (surely not without force) to start working in Japan. These originally Korean methods eventually became the styles of Arita-yaki and Satsuma-yaki (among others).

Tableware made of ceramics and porcelain

Before concentrating further on the distinct manufacturers and manufacturing styles/methods of Japan, this is a good point to clear up the differences between ceramics and porcelain. Ceramics consist of clay that is burned at relatively low temperatures (800 – 1200°C) over a long time. Contrary to that, porcelain consists of certain minerals (kaolinite, feldspar and quartz) that are pulverized, mixed together with water and then brought into the desired form. The mixture is then also burned, but shorter and at higher temperatures than ceramics (1200 – 1400°C).

After burning, ceramics naturally have a rough texture (that is often smoothened with glazes), whereas porcelain naturally has a rather smooth surface. Due to the way the materials are manufactured ceramics are often times thicker and bulkier, porcelain on the other hand thinner and lighter. Of course, there are always exceptions. Tobe-yaki, for example, is porcelain with a bulky style. This may also be a good point to explain the suffix of -yaki that’s in every name of a manufacturing style. Yaki (焼) literally could refer to anything “burned” (or in the sense of food it can mean “fried”, like the delicious Japanese dish okonomiyaki). Knowing that it’s easy to see why this suffix has been established in the context of pottery.

15 famous manufacturing methods:

1. Yachimun from Okinawa

Okinawa is the southernmost prefecture of Japan and thanks to its tropical climate a favourite holiday destination for the Japanese. For international tourists though the coral reef lined shores of Okinawa are not yet that well known. Fitting Okinawa’s location inbetween China, Taiwan and Japan, its original (Ryūkyū) culture is a mix of Chinese and Japanese influences.

Origin of word Yachimun

The name yachimun is Okinawan dialect for the Japanese word yakimono, which means “burned things” and refers to all pottery. In Okinawa, yachimun refers specifically to all pottery made by Okinawan artisans with local materials and methods. Yachimun-yaki is usually made of red clay. After it’s burned, the ceramic is sprinkled with a white powder, burned again, painted with colored glazes and then burned a third and final time. Popular patterns are florals of vines that represent strength and positive energy, as well as fish, which represent fertility. Over twenty yachimun manufacturers are concentrated in the district of Tsuboya in Naha. If you’re a lover of ceramics (which, considering you’ve read the article this far, you are), the place is definitely worth a visit!

Satsuma Yaki from Kagoshima

From Okinawa, it’s quite a distance to the main islands of Japan. We travel by boat or plane to the southern tip of Kyushu. After many smaller islands we arrive at Kagoshima prefecture. The region is famous for the sand onsen of Ibusuki, the meat of black pigs and – of course – its ceramics, in the form of satsuma-yaki. Until a name change in 1872 the prefecture was known as Satsuma, which is why the old name can still be found on many local products.

There are two main types of satsuma-yaki: the original, sober design of kuro-mon (black ceramics) and the lavishly decorated shiro-mon (white ceramic). The appendix “mon” is dialect for the Japanese word “mono”, meaning “thing” or “object”. Production of the latter, white ceramic started after the opening of Japan in the mid 19th century, with the explicit goal to make the products appealing to western customers. This resulted in fine and elaborate paintings on the pottery in striking colors such as gold.

During the Meiji era shiro-mon gained popularity and soon was exported in great quantities. In 1867 – at the world exposition in Paris – shiro-mon was presented. In the artistic fever of japonism that was gripping Europe in the late 19th century (especially France), the ceramics from Kagoshima rapidly gained popularity. Under the name of “Satsuma” it became well known in all of Europe.

3. Ryumonji-yaki from Kagoshima

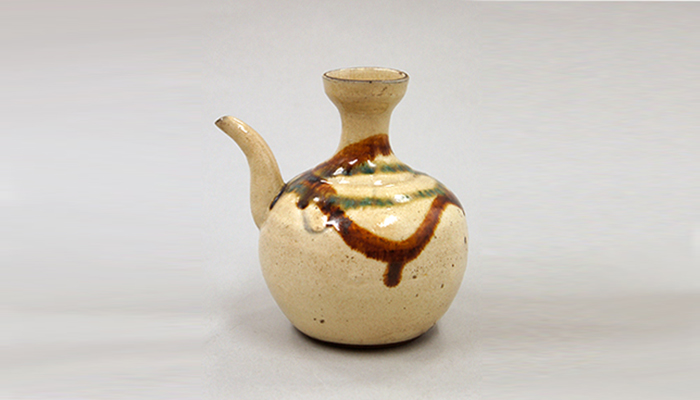

The other well known manufacturing method from Kagoshima prefecture is ryumonji-yaki. To be exact, it is a variation of satsuma-yaki, with the difference lying in the style of glazing and ornamentation. While shiro-mon is painted with fine brush strokes forming complex patterns, ryumonji-yaki has thick glazes of green and brown color that are poured over the ceramic. This leads to unique patterns on every piece of pottery, sometimes showing strong drop patterns. In Japanese the technique is called “sansai-nagashi”, meaning “pouring with three colors”. A popular ryumonji-yaki product is a sake bottle with a small sphere inside it. When the bottle is empty, shaking it makes a clicking sound, signalling that it’s ready to be refilled. A similar bottle can also be found for soy sauce.

4. Hasami-yaki from Nagasaki

From Kagoshima onwards our journey continues north. The way leads through hilly terrain and many small villages with surrounding rice paddies until we arrive in Kumamoto, in the center of Kyushu. From there, a boat takes us to Nagasaki (for more information on Kumamoto you can refer to station no. 7 of our pottery journey). Nagasaki is a city with a long history in trade, also thanks to the outpost of the Dutch East India Company stationed there during the Edo period. During that time period, Nagasaki was the only place in Japan where there was some sort of regular contact with western culture.

Deep in the north of the prefecture (close to Saga prefecture) lies the small town of Hasami surrounded by mountains. The inconspicuous city is a hotspot for porcelain lovers, drawing a yearly number of 800.000 tourists to its workshops and stores. 300.000 people alone visit during the yearly porcelain festival in spring (March or April). 30-40% of the working population of Hasami is in the porcelain business in one form or another.

Typical properties of hasami-yaki

Hasami-yaki is most well known for indigo blue colors on light and white porcelain. In contrast to other styles of porcelain, there are no unique patterns that define the style of hasami-yaki. Instead, the strong point of hasami-yaki comes is its variety with patterns that change from year to year. The porcelain is relatively cheap and therefore popular to use as everyday tableware. In Japanese it’s sometimes called “o-uchi shokki” (home dishes).

5. Arita-yaki from Saga

Just a few kilometres north of Hasami lies the city of Arita. Arita belongs to Saga prefecture. The area is (besides its pottery) known for a hot air balloon festival and the Karatsu-Kunchi-Matsuri (a religious festival celebrating a mountain god), both being held in late October to early November.

Arita-yaki is partly similar to hasami-yaki: It also usually shows indigo blue colors on white porcelain and isn’t restricted to certain types of patterns. It is possible though to discern by whom and when a piece of pottery was produced, thanks to trends in the styles of the patterns. Especially the works of artist Kakiemon stand out from the rest. He uses red, instead of the traditional blue color used in arita-yaki. His unique style has the name “Akae”.

In former times arita-yaki was shipped to other Japanese cities and foreign countries via the nearby port of Imari. Therefore, arita-yaki was also called imari-yaki in the past. Nowadays the name arita-yaki is well established though.

6. Koishiwara-yaki from Fukuoka

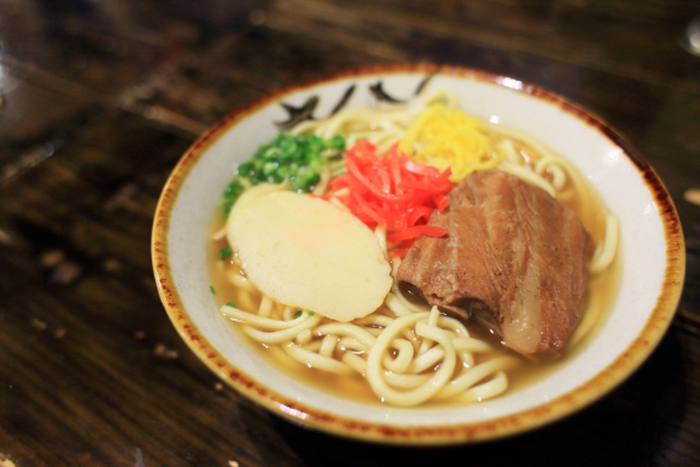

Following the coastline from Arita to the north, we arrive at Fukuoka prefecture. Here we find beautiful beaches (in Ito-shima) – the likes of which also exist in the mediterranean – and old temples in Dazaifu. These places feel like how you would imagine a “real” Japan without all the tourists: Old tea houses made of dark wood, people walking around in kimonos and snacking on hand made yaki-mochi. The metropolis of Fukuoka, Hakata district to be exact, is also well known for strong flavored tonkotsu ramen. In Nakasu quarter a road near the river is completely filled with small stalls (yatai) which sell fresh, steaming ramen until deep in the night.

Koishiwara and Onta

There are high plains in rural Fukuoka, surrounded on all sides by mountains, with the name of Koishiwara. This is the birthplace of Koishiwara ceramics, which originated there more than 350 years ago. Koishiwara-yaki is made from the local beige colored clay. Nowadays around 56 manufacturers of koishiwara-yaki exist. Similar to onta-yaki, a pattern of dashed ornaments is what makes this ceramic stand out. In fact, onta-yaki developed out of koishiwara-yaki at around 1700 CE, which brings us to our next type of ceramic.

7. Onta-yaki from Kumamoto

Not far from Koishiwara is the border between the prefectures of Fukuoka and Kumamoto. There we visit the village of Onta, which gives onta-yaki its name. Pottery has been produced in Onta since the early 18th century. As mentioned above, onta-yaki is similar to koishiwara-yaki, probably not at least because of the small geographic distance between the two places. Onta-yaki can be distinguished by the use of grey clay as its raw material and a tight dashed pattern. That pattern is either notched into the material (a method called “tobikanna”) or painted on with a brush when the ceramic is being glazed (a method called “hakeme”). Today there are still ten different workshops producing traditional onta-yaki. SInce 1995 this pottery has been designated a national cultural heritage.

8. Tobe-yaki from Ehime

Leaving the lovely rural Kumamoto we journey on to the harbor that will take us across a small straight in the Japanese Inland Sea. The harbor where we stop is, of course, the onsen mecca of Beppu. So our only logical choice is to first soak in the hot springs there before we step onto a ferry for Shikoku. Shikoku is the fourth biggest Japanese island and all the way to the west of that island lies Ehime prefecture, our next destination. To be able to fully appreciate the pottery there without any disturbances from our stomach, we try the excellent local specialities of Udon, Taimeshi (rice with sea bream in soy sauce and sesame). Both of them are delicious, so there really is no wrong choice.

But back to the main topic, we visit the small town of Tobe near the provincial capital Matsuyama. Its main product, tobe-yaki, can be found everywhere! As paving blocks on the road, mosaics on walls or street signs, there is no escaping the white and blue porcelain.

Tobe-yaki = “Kenka-yaki”

The stone used as raw material tobe-yaki is being mined in a quarry near the town. The resulting porcelain has a unique thickness. Tobe-yaki is therefore jokingly called “tableware for fighting” (“kenka-yaki” in Japanese). Because even when a couple’s quarrel gets passionate, it is said that you can throw the sturdy porcelain without breaking it. We do not endorse trying this at home though. Typical hand painted patterns of tobe-yaki are vines, nazuna-flowers or mitsumon (a classical family crest often found on men’s kimonos). The brushwork is usually delicately curved. Tobe-yaki is mostly glazed with an indigo blue color, whilst sometimes showing bright red or turquoise details. There are over 100 manufacturers in Tobe, reflecting the popularity of the porcelain. Hopefully it’s popularity is due to the use as tableware and not for throwing it in the middle of heated discussions.

9. Bizen-yaki from Okayama

Okayama is located close to Ehime on the main island of Honshu. From Ehime we take the road north and pass the scenic Shimanami-Kaido road. This series of bridges connects many small islands in the Seto Inland Sea between Shikoku and Honshu and is a highlight for everybody who wants to do cycling in Japan. After arriving in Onomichi in Hiroshima prefecture it is only a short way to Okayama. A well earned break from travelling includes a dish of unagi-don, some peaches and a stroll through one of the three most famous gardens in Japan: Gorakuen.

The region of Bizen lies east of Okayama city. Ceramics have been produced here since around 800 CE. That makes Bizen the second oldest of the “six ancient kilns of Japan” (“Rokkoyō”), after Tokoname (in Aichi prefecture), which is the oldest. Bizen-yaki has a characteristic dark red to brown color and uneven surface texture. A particularly long burning process of ten days in a hot flame (1200-1300°C) makes this ceramic particularly strong and robust. Typical products of bizen-yaki are therefore mortars, large carafes and pots. The center of the production of bizen-yaki is the city of Inbe, which today is part of the Bizen region.

10. Tanba-yaki from Hyogo

From Bizen it’s not far to Hyogo prefecture, home to not only the magnificent Himeji castle, but also to the port city of Kobe. Kobe can boast a special international flair since the Meiji period, with a sprawling harbor and Chinatown. On a walk through the northern parts of town you might notice many buildings with European architecture. Complementary to the architecture there are many restaurants offering French, Italian, Spanish or German cuisine. Unmistakingly the most famous dish from Kobe is “kobe wagyu”, or Kobe Beef. The designation wagyu (Japanese beef) only refers to certain strains of Japanese cattle whose meat is rich in finely marbled fat.

In the mountains of Hyogo

Our destination is the small town of Tamba. Following a curvy road northwards from Kobe, we arrive at the birthplace of tanba-yaki about an hour later. This Ceramic is produced from red clay and glazed with white-grayish or brown colors. A typical motive often carved into the clay itself is chrysanthemum flowers or shrimps.

Tamba can proudly refer to its long history of pottery-making, making it a member of the exclusive group of the “six ancient kilns of Japan”. The official name of the ceramic is “tanba-tachikui-yaki”, but most people shorten the name down to “tanba-yaki”. There are still 60 manufacturers in Tanba, which practice the classical way of producing pottery. Every year, on the third weekend of October, a ceramic festival is being held, where the manufacturers present their work.

11. Shigaraki-yaki from Shiga

Next stop: Kansai region. We have to cross many mountain passes, rivers and valleys, but finally we arrive at Lake Biwa, the largest fresh water lake of Japan (we’re skipping the densely populated area of Osaka and Kyoto). To get an overview of the lake, we take the ropeway up to Biwako Terrace, an observation deck at a height of 1100 m above sea level, located on a mountain shoulder and overlooking the prefecture of Shiga.

Besides great nature, there are the castles of Azuchi and Hikone to visit, remnants of the Warring State Period (16th century). After refreshing our knowledge of medieval history, we venture on to the small town of Shigaraki, southeast of Lake Biwa.

The 10.000 tanuki of Shigaraki

In Shigaraki we are presented with thousands (if the local tourist information is to be believed: ten thousand) of tanuki statues. Statues of tanuki (racoon dogs in English) are often believed to bring prosperity and wealth, and can therefore often be seen standing in front of shops or restaurants. They are the most popular export of shigaraki-yaki. The local clay can be easily formed thanks to its flexibility. That enables a large range of products. Even though shigaraki-yaki is famous for its tanuki, it too has a long history of ceramic production and is also part of the “six ancient kilns of Japan”. In former times the townspeople mostly manufactured everyday tableware, like cups, plates and mortars. Early products of Shigaraki from the 8th century are said to be influenced by bizen-yaki, but the exact timing and manner of the influence is hard to pin down.

12. Tokoname-yaki from Aichi

We are going further east, through Mie prefecture and into Aichi prefecture, which is dominated by the metropolitan area of Nagoya. This region is one of the three largest centers of commerce and production in Japan (after Tokyo and Osaka) and is home to companies like Toyota. Besides lots of industry, sightseeing plans can include the Atsuta shrine or Nagoya castle, which are both well worth a visit.

The local kitchen can make your mouth water with intense miso dishes, like miso-katsu (pork cutlet in sweet miso sauce) or miso-udon. On the eastern side of the bay of Ise, near Nagoya airport, lies Tokoname. Similar to Shigaraki, Bizen and Tanba, Tokoname is has a long history of ceramic production (and is part of the “six ancient kilns of Japan”). The kiln furnaces themselves are special in Tokoname. Since the Meiji period (late 19th century) the kilns are built inside the hillsides, so that the convection of air is used to maintain high and steady temperatures. Around 60 of such hillside kilns exist in Tokoname, one of which – built in the Showa period – is the biggest kiln furnace in all of Japan.

Tokoname-yaki has a red-brownish to beige color. It’s design is often simple with many straight lines. Even though tea cups and plates are also produced, the focus of tokoname-yaki manufacturing lies on larger products, such as pots and mortars.

13. Seto-yaki from Aichi

After visiting Tokoname we stay in Aichi, but move on to the north of Nagoya. This is the fifth and last of the “six ancient kilns of Japan” we are visiting on this journey (we are skipping echizen-yaki on this trip). Nowadays there two different ways of manufacturing seto-yaki, or seto-mono, as it is sometimes called. The first way is the traditional one, resembling other old ways of ceramic manufacturing we have presented so far. The second one is the modern one, showing european influences and sometimes having more experimental shapes.

Manufacturers of seto-yaki were the first Japanese to widely use glazing in their work, making them sort of pioneers in the world of ceramics. From Seto the art of glazing ceramic spread all over Japan.

14. Mino-yaki from Gifu

To get to Mino in Gifu prefecture, we have to go deeper into the mountains, to the outer edge of the Japanese Alps. Most of Gifu is far away from big cities and crowds of tourists. We are left with lots of nature, high mountains and Japanese locals. There are hardly any foreigners or English speakers here, so when travelling here it’s recommended to come with a Japanese friend or guide, or to be able to speak Japanese yourself. Otherwise communication might prove difficult.

Still, rural Japan has its own charme and overflows with beautiful spots, so we definitely recommend visiting the “inaka” (countryside in Japanese). North of Mino (a bit further than we have to go, but well worth the detour) the district of Sanmachi in Takayama makes you feel like a time traveller: Streets are lined with original Edo period houses. If people weren’t wearing modern clothing, one might think that nothing has changed here in the last 200 years. Local specialities are yakiniku (barbecued meat), steak and dango (small rice balls in sweet sauce).

Seto and Mino

Mino-yaki is closely related to seto-yaki, because it developed from seto-yaki. During the warring states period some masters of ceramic production fled to Mino and settled there. The local Daimyo (feudal lord), Furata Oribe, took them under his protection. He ordered the production of a new type of pottery and (“humbly”) coined it oribe-yaki. During its early days, Oribe-yaki from Mino was getting popular for its use in tea ceremonies. But after the early Edo period (after ca. 1600) the focus shifted towards the ceramics for every day use.

Today’s mino-yaki is very versatile and does not have one singular defining feature. It is not defined by certain colors or patterns, and the way of producing it does not differ from the regular way of producing pottery. Simply put, mino-yaki is a mass product, which is why around 50% of all ceramic sold in Japan is from Mino. That makes it especially important to know about mino-yaki. Because – if you are in Japan – at one point or another, you will likely have a tea cup from Mino in your hands.

15. Kutani-yaki from Ishikawa

A few mountain roads lie between Mino and the last station of our ceramic journey through western Japan: Kanazawa in Ishikawa prefecture. Located at the coast of the Japanese Sea, the city is famous for good seafood like kaisendon. A last afternoon of sightseeing takes us to the castle of Kanazawa with its famous Japanese garden Kenrokuen. After ticking these stops off our bucket list, we can spend some time with kutani-yaki.

Kutani-yaki is different from everything we have seen so far. It is a porcelain that is colorful, playful and dynamic. Patterns range from traditional florals to skeletons to Converse shoes. Landscape or animal patterns are also popular. Oftentimes you can find well-known Japanese designers collaborating with the producers of kutani-yaki. While the patterns may be very colorful, there are five characteristic colors for Kutani-yaki, called the “kutani gosai”. Those are red, yellow, green, violet and dark blue. Kutani gained a lot of popularity in Europe after the World Fair of 1873 in Vienna. Especially the coloration fascinated many visitors at the time.

Ceramic as an export product

The different types of Japanese ceramics and porcelain are still exported and sold all over the world. They have a reputation of excellent quality and design, but that wasn’t always the case. The popularity of Japanese pottery nowadays resulted from the work of ceramic manufacturers and artists like – among others – Yanagi Soui, Bernhard Howell Leach, Kawai Kanjiro and Hamada Shoji, who especially popularized koishiwara-yaki and onta-yaki outside of the borders of Japan.

Published: 04.08.2020 | Posted by Colin